By Lindsay Gandolfo

It all started in Venezuela 19 years ago, when transplant surgeon and Chief of Abdominal Organ Transplantation Tomoaki Kato, MD met Venezuelan transplant surgeon Pedro A. Rivas Vetencourt, MD.

Dr. Kato was a surgeon in Miami at the time, trying to help a local mother raise money to bring her very sick child from Caracas to the U.S. for a living liver transplant. Living liver transplant is a procedure that uses a segment of the liver from a living donor to replace the recipient’s diseased liver, where it grows to size. Due to astronomical costs, they couldn’t find the money to treat the child in the U.S., prompting Dr. Kato to say: “Maybe I can find somebody and we can do the transplant in Caracas.”

By 2004 in Venezuela, liver transplant in adults was established but there was no program anywhere for children. “I started calling my friends from Venezuela and somehow, miraculously, in the same day I was talking to a surgeon in Caracas who really wanted a surgeon like me to help them start a pediatric liver transplant program,” says Dr. Kato. That surgeon was Dr. Rivas.

Dr. Rivas participated in the first-ever liver transplant in Venezuela in 1992 and went on to create the first permanent liver transplant program in the country. Eight years later the Metropolitan Program of Liver Transplantation – FundaHígado – was born, transforming the landscape of Venezuelan medicine by teaching transplant surgery to physicians in the region and ushering in a new era of abdominal transplant care.

Both respected pioneers in their own countries and both boundlessly passionate about saving lives, Drs. Kato and Rivas quickly found a natural partnership. Dr. Kato flew to Caracas in December of 2004 and met with the baby and parents. “We decided to do the live donor transplant, the father being the donor. So, we scheduled the surgery for January and I went back to Miami. But the baby died on Christmas Day,” says Dr. Kato. “We couldn’t save that child.”

On rare occasions, such tragedy finds a way to beget a blessing. Word spread fast about an American surgeon who was invited to Venezuela to do pediatric transplant. It wasn’t long before another very sick child from the city of Maracaibo appeared on Dr. Rivas’ doorstep.

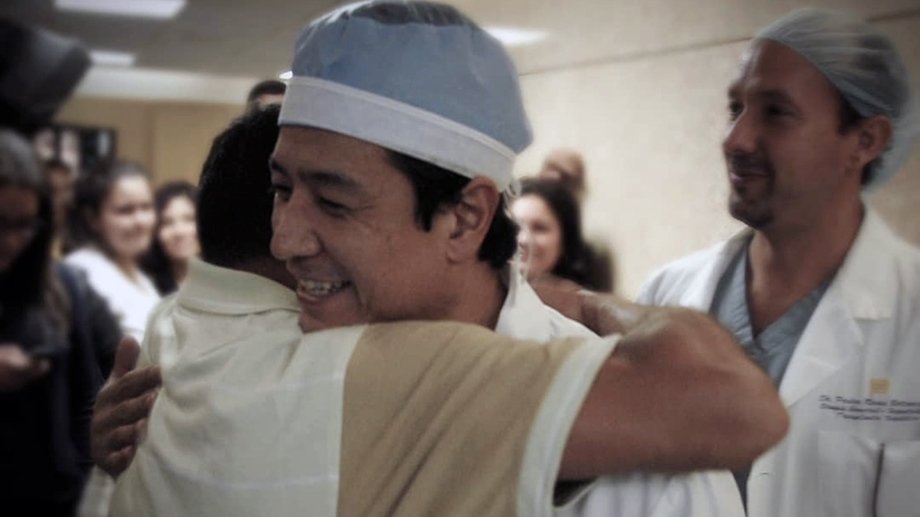

That child successfully received the first pediatric liver transplant in the country. Right away, Dr. Kato and Dr. Rivas established precedent, protocols, and began teaching surgical teams how to do transplant operations on children and live donors. To date, through their organization FundaHigado America, hundreds of Venezuelan children now have a new chance at life.

A Blueprint for Change

“It was a very successful program,” says Dr. Kato. “So, around the time I came to New York, Dr. Rivas and I had the idea: maybe we should replicate this in other countries.”

Today, even in 2023, there are many countries with zero access to lifesaving pediatric liver transplants—like Nicaragua, Panama, El Salvador, Haiti, Guatemala, and until recently the Dominican Republic. From lack of financial support and surgical education to no organizational structure on which to build surgical programs, nearly every child in need of a liver will die because their country’s borders denote no access.

It’s not uncommon for surgeons from countries with poor healthcare to come to large institutions like NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia and learn complex procedures with the intent to establish programs back home. But it doesn’t always pan out.

“That was an interesting thing we learned along the way, that if we just mimic whatever we are doing in America it’s never going to work,” says Dr. Kato. “We have huge resources to do pediatric liver transplant—pediatric ICU nurses, anesthesiologists, everything. They’re never going to get the same level of resources we have here… the same care of the child after.”

The model that Dr. Kato and Dr. Rivas developed feels thoughtfully simple and remains uniquely complex. Go to the country, look at all the resources available, and develop the support within their existing capacity to build a new program from scratch.

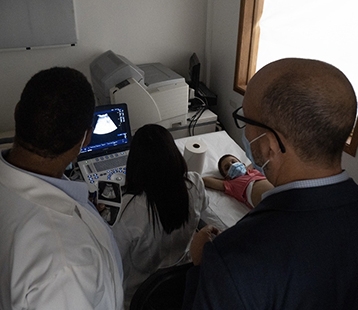

In Caracas they started first by training an anesthesiologist, a pediatric intensive care unit, radiologists, and ultrasound technicians—All the pieces required to complete a successful transplant. They were also able to find monetary resources through government support.

“We don’t want to just treat rich people’s children,” says Dr. Kato. “So, we negotiated with the government [in Caracas] to do it in the private hospital but have the government fund the program so we don’t discriminate against any child.”

Empowering Lifesaving Care from Within

When Dr. Kato joined the faculty at NYP/Columbia in 2008, he met Mercedes Martinez, MD, pediatric hepatologist and Medical Director of the Intestinal Transplant Program. Dr. Martinez had aligned passions; working with institutions in Florida, organizations in the Dominican Republic, and government agencies to create access to liver transplants for kids in the Dominican Republic.

“People with money have international insurance and can go out of the country [for transplant] and pay for everything,” says Dr. Martinez. “Poor children of the Dominican Republic are the ones that are dying without the option of having transplant.”

It was hard work with little success in funding. But Dr. Martinez kept at it, joining forces with Dr. Kato and FundaHidago America. On her first hospital call to the Dominican Republic, she was invited to give a lecture on pediatric liver transplant. That hospital wanted to start a program but because the adult liver program just got off the ground, resources were few and capacity limited. They had to find somewhere else.

Over the next six years, the Fundahigado team made many trips to the Dominican Republic. Meeting with government officials and policymakers, hospital leadership, and even the First Lady to create state-led support for the program and secure funding to buy the necessary equipment and cover transplant costs.

Most importantly, Dr. Kato and Dr. Rivas needed to identify the right surgeon to run the program and build the team on the ground. With resources and a team in place, the Hospital General De La Plaza de la Salud in Santo Domingo agreed to do pro bono transplants in children, with continued support for the kids and their families through government funding.

“So first, we fly the doctors and nurses to Caracas to watch how they're doing it in Caracas. They transplanted together in Caracas first, then went back and did the first case in the Dominican Republic,” explains Dr. Kato. “And then, for the second case, we just focused on the local team.”

“This model of going there and training locally, I think it’s a very unique and interesting model. It takes more time, but it gives the local doctors a chance to improve their skill, get cutting-edge liver transplant surgery done in their country,” says Dr. Kato. “Makes it possible.”

So far, they have done two pediatric liver transplants in the Dominican Republic, the first in a young girl named Raquel in 2021 and another earlier this year in a 7-year-old boy named Eliezer. Dr. Kato, Dr. Rivas, and Dr. Martinez were all there to plan care, do pre-op evaluations, complete the procedures, and do initial post-op care. Flying down on the weekend to operate and back home to see patients the next week.

Care and training don’t stop from afar either. For each case, they continue to work with the doctors and ICU unit on the ground until their patient is discharged and continue for all follow-ups. “I was talking to the team there every day,” says Dr. Martinez. “Sometimes multiple times a day.”

Well-trained Teams Have a Cascading Effect on Healthcare

There are wider benefits to medical treatment too. “It’s more than just doing transplant. They’re now able to do other things with the same resources,” says Dr. Kato. “The same team we built in D.R. is capable of doing many other pediatric surgical procedures more efficiently.”

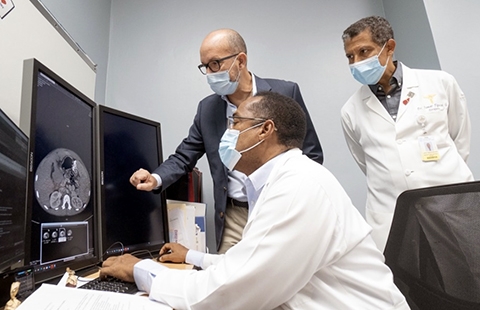

“We’ve seen the quality of the radiology department improve significantly because the kind of images needed to evaluate the living donor and diagnose post-transplant complications are above the standard the country used to have,” says Dr. Martinez. “The hospital had to buy new CT scanners. Now, anybody that comes to that institution can benefit from those radiologists learning from our radiologists. This has elevated the care that this hospital can provide to the general public.”

The next big hurdle is to get sustained government funding instead of working case by case. “The first lady is so energetic, she gets it. And she really wants to work with us,” says Dr. Kato. “So I think the program is going to grow.”

And if anything is clear with this group, growth knows no borders. Doctors and nurses from El Salvador joined the most recent transplant in the Dominican Republic. That’s where Fundahigado plans to work next

“Our hope is really to do this in each country. It may take a while. Each country may take five years to do,” says Dr. Kato. “But it’s really a worthwhile effort.”

You can support the work of FundaHigado and learn more about all they do here.