Editorial note: This interview was reviewed and updated by James Lee, MD, January 2024.

An interview with James Lee, MD, Chief of Endocrine Surgery.

Key Topics:

Let’s start with a basic one: what types of surgery are covered under the term “endocrine surgery”?

It's funny you mention this because the national society that Jenn Kuo and I belong to is called the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, and one of our big pushes is actually to tell people exactly what endocrine surgery is. So, in general, we define endocrine surgery as professionals who take care of thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal, and neuroendocrine disease or disease of the pancreas or the GI tract.

There’s also an emerging field called interventional endocrinology housed there too. Will you explain what interventional endocrinology is?

Interventional endocrinology basically means percutaneous ablation of thyroid nodules. So, we put a needle through the skin, and we destroy the nodule from the inside out using different types of thermal technologies. The reason interventional endocrinology is important is because 30 to 40 percent of Americans will have a thyroid nodule. Most of them are benign and most of them don't need much to be done except for follow-up with ultrasounds. Having said that, probably about 20 percent of those patients who have a thyroid nodule will need some sort of intervention. And probably about 10 percent of those patients end up having an operation. Of the patients who have thyroid operations, probably 20 percent can actually have interventional endocrinology done with it.

Are those interventional options all in-office procedures?

Yes, exactly. We do it right here in our office as an outpatient. You walk home five minutes after the procedure is done.

So interventional endocrinology is going to become the cardiac stent of the endocrine world. It's going to be a very minimally invasive, the truly minimally invasive way of addressing a huge volume of thyroid nodules.

Thyroid

Thanks for clearing that up. What conditions fall under the umbrella of thyroid disease?

Thyroid surgeons take care of the gamut of thyroid disease. Thyroid nodules, for example, are incredibly common. Up to 30 to 60 percent of Americans will have a thyroid nodule detectable by either a physical exam or an ultrasound. And the vast majority of those nodules are benign.

Then there are the malignant diseases, obviously cancer at lots of different strengths. In general, the vast majority of thyroid cancers are very good prognosis cancers. We always say it's the best cancer to have because the prognosis is so good, but it also encompasses some of the deadliest cancers known to man. There's a very, very rare thyroid cancer called anaplastic cancer, which is almost uniformly fatal. Thyroid disease really spans the gamut of malignancy.

And then there are diseases of thyroid function—underactive thyroids and overactive thyroids. In general, surgeons don't treat patients who have underactive thyroids, which is called hypothyroidism. In contrast, with hyperthyroidism, we operate on a fair number of those patients in order to control their thyroid disease. Surgeons actually create a lot of hypothyroidism because we take out thyroids to treat a hyperthyroid, and therefore by definition, they are then hypothyroid.

When you say you don’t treat underactive thyroids, what are the management options for people with hypothyroidism?

Oh, it’s a good question. The tried and true management for hypothyroidism is a thyroid hormone called Synthroid or levothyroxine. Just a man-made form of thyroid hormone, and that treats it very well.

What’s new in the treatment of thyroid diseases?

Number one is active surveillance. Meaning, in general, as a field we're getting much less aggressive at treating thyroid cancer or thyroid disease. For example, 5, or 10 years ago, with thyroid cancer, everyone would get their whole thyroid taken out—called a total thyroidectomy. In 2015, the American Thyroid Association released new guidelines saying that taking out half of the thyroid is probably adequate for small cancers. And active surveillance, what Hyesoo Lowe is building on at Columbia, is the notion that for very small thyroid cancers—less than a centimeter and a half in size and without aggressive features—patients can actually be observed because most of them don't have a disease that is going to hurt you.

With active surveillance, when and how do you decide if it’s time to surgically intervene? Are there specific indicators?

In many patients who have thyroid disease that's going to progress we can pick it up with an ultrasound and active surveillance and proceed from there. On the benign side, we're also trying to be less aggressive with surgery. As I mentioned, thyroid nodules are very common and there are lots of reasons to take out thyroid nodules: if they're hyperactive, if they're very large, if they're causing compressive symptoms, a choking sensation when they lie flat. Food gets stuck in their throat when they're eating. Difficulty breathing. And then some people have a big nodule and don't like the cosmetics of it. In those scenarios, we typically will take out part or all of the thyroid. That’s where interventional endocrinology comes in.

What kind of thyroid nodules can be treated with interventional methods instead of surgery?

Currently, we're only using it for benign thyroid nodules. But our group is conducting the clinical trial where we're looking at thyroid nodules that have an increased risk of thyroid cancer, a group of nodules called indeterminate lesions. And those lesions tend to have about a 20 to 30 percent risk of thyroid cancer. Small thyroid cancers that are less than a centimeter and a half are considered microcancers, and currently, a lot of people are actually having those removed in an operation. But we know that those really small cancers, especially in people younger than 50, don't hurt them. So, we're probably doing too much surgery. The real magic of this technology is going to come in when we can prove that interventional endocrine is just as effective as an operation in treating those small cancers.

What are the benefits of interventional endocrinology methods over surgical procedures?

It’s less invasive, requires less stuff, like general anesthesia. Recovery is faster. The other important thing is that if I take out half of your thyroid, which is the general treatment for microcancers, there's about a 20 percent chance you're going to need lifelong thyroid hormone supplementation. This means that you'll have to take one pill a day for the rest of your life just to supplement what the other remaining thyroid is doing.

With interventional endocrinology, the rate of hypothyroidism is much, much less. So probably three to five percent need thyroid hormone after interventional endocrine. If we can prove that interventional endocrine techniques are as good as surgery for small cancers for low risk lesions, it's going to help a huge swath of people avoid surgery.

How are these microcancers first discovered?

Great question. Overwhelmingly, people have an ultrasound for some reason. Sometimes it's because they're symptomatic. Sometimes the physician feels a nodule on an exam, but it almost always starts with an ultrasound of the neck, that identifies a thyroid nodule. There's a specific set of guidelines that basically decide which nodules need to be biopsied and followed.

Interestingly, currently, the vast majority of patients who are getting interventional procedures are self-selecting. They see their docs, they get a recommendation to have an operation, and they do an internet search and find interventional endocrine, and ultimately they find Jen Kuo.

Let’s talk about these interventional methods for benign nodules. What are they?

First is radiofrequency ablation, or RFA, where we’re able to target the nodule and spare the surrounding tissue with a non-surgical outpatient procedure. And Jenn Kuo is the leading figure in interventional endocrine in the United States and one of the world's experts in this. Because of Jenn, Columbia is one of the designated training centers for interventional endocrinology. She’s traveled all over teaching the procedure. In fact, every Canadian who currently does this procedure has actually trained with Jen.

Wow. Radiofrequency ablation sounds like a real game-changer. I’ll link to our interview with Jenn Kuo on RFA here, but quickly, what is the most significant benefit of this new treatment?

Okay, if I take out half of your thyroid, there's about a 20 percent chance you're going to need to take thyroid hormone replacement or supplementation because the other side isn't enough to keep you healthy. The hope is that with RFA, since we don't have to take out any normal thyroid tissue, you’d still have plenty of thyroid hormone. So, the rate of hypothyroidism will go down after that procedure.

Any other big changes to the treatment of thyroid disease in the last 5 to 10 years?

There’s one more that I think will have a real, lasting impact—the transoral thyroidectomy. In transoral thyroidectomy, you make an incision behind your lip in front of your teeth. And you use laparoscopic equipment and take out the thyroid by stretching the neck and going down that way, leaving no visible scar at all. There's a surgeon in Thailand who really popularized the technique and has done probably thousands of them at this point.

It's part of a whole field or school of thought in thyroid surgery called remote access surgery. Experienced thyroid surgeons do what we call minimally invasive thyroidectomies, where we make small incisions and take out the thyroid through those small incisions. And it really started, as most of these new innovations do, in Asia. They started taking out thyroids through your armpit. There’s also one called the facelift thyroidectomy, where we make an incision behind your ear like you would for a facelift. But the one people are really excited about is transoral. We do it here at Columbia, but it still hasn’t taken off in the United States yet. There are only pockets of places in the United States where people do transoral thyroidectomy.

From your perspective, is one remote access technique better than the other? Why are you most excited about the transoral technique over the others you mentioned?

In my mind, when you are thinking about remote access surgery, the outcomes have to be equivalent and the cost has to be roughly equivalent in order to make it really worthwhile. Again, because, in general, we can make an almost invisible scar using the standard approach.

The problem with things like the transaxillary [armpit] approach is that there is not the same risk of complications as when we do it as a traditional open operation, there are additional complications. Infection rate is much higher. You can have neuropathy in the flap that we make. All these other things can happen. And the cost is much higher because the operations are longer, you're going through the armpit and you're using the robot. For those reasons, the technique never really caught on.

I think the reason people are excited about the transoral technique is that it's a much more direct route. The cost is a bit more, but it's palatable because usually, you're using laparoscopic equipment, so there's not a huge increase in cost. The operative times in good hands are longer, but they're pretty good. So, to answer your question, I think if, as a society, we're going to offer these remote access operations—and I think we should—they should be comparable in terms of complications and cost.

What does long-term recovery look like for remote access operations?

If you go through the armpit, it's a longer recovery. The transoral seems like they have pretty good recoveries, pretty quick. But there are always unintended consequences that you have to take into account. One of the things to consider for people who have very nicely defined chins is when they have a transoral, oftentimes their chin gets widened out because you're making a tunnel right through the plane. Those aren't necessarily things that you can plan for because you don't know how it's going to look after the fact. So, it’s important to discuss expectations and desires around cosmetic results and really weigh the potential risks.

Dr. Kuo is actually our local expert for the transoral thyroidectomy. We went to see that surgeon in Thailand and spent a week operating with him there to learn how to do the technique.

One last thing I want to ask about thyroid cancer is the increased risk of thyroid cancer warnings on drugs like Ozempic. Can you shed some light on that?

Yes, Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro—semaglutides are the class of drug. For all those medications, if you read the label, it says that there's an increased risk of thyroid cancer. An important thing to note is that the thyroid cancer they're talking about is a specific type of cancer called medullary thyroid cancer, which is incredibly rare.

So they say don't use Ozempic if you have a history of thyroid cancer, but it's that specific type of thyroid cancer called medullary cancer that is by far a less common cancer than the other ones. The most common type of thyroid cancer is papillary cancer, and there's really been no association shown or worsening of papillary thyroid cancer with Ozempic.

Parathyroid

Let’s jump over to parathyroid management. Is there anything new in the treatment of parathyroid disease?

I would say that for parathyroid disease, it’s the realization that the pendulum is starting to swing back. In general, the field has always been a little bit more conservative about offering parathyroid surgery to patients. Even if patients had high calcium levels (a normal calcium level is up until 10.2 roughly), for many, many years patients didn't get referred for parathyroid surgery until their calcium was in the 11s. And in that gray area of 10.2 to 11 oftentimes there are primary care docs or whoever was taking care of them saying, "Now, watch this. It's mildly elevated, why don't you just watch it? Why have an operation?"

But we realize as we concentrate on these parathyroid operations in the hands of experts, the complication rates are getting better, and the outcomes are getting better. More and more people with mild disease are going for operations and appropriately so. That's one of the big trends and one of the big things that, as endocrine surgeons, we want to really promote.

In endocrine surgery, there is a huge amount of literature showing that the more you do thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal surgery, the better your outcomes are. Patients have fewer complications, they recover faster, operative times are shorter, cost is less. So that's one of the big pushes for endocrine surgeons is to really get that out to the public: experience matters.

I would imagine that along with that experience, getting access to some of the state-of-the-art and less invasive treatments matters too.

Yes, yes, exactly. I bet if you had a three-centimeter benign thyroid nodule and you went to a surgeon not at an academic center or not at a high-volume center, you'd never hear about RFA and you’d get your thyroid taken out.

And the same with Dr. Lowe’s active surveillance program. If someone says, "Oh, you have biopsy-proven cancer, it happens to be seven millimeters." It's still cancer you're going to take it out because you assume you have to. That’s where experience and expertise really come in.

Will you explain tertiary or secondary hyperparathyroidism?

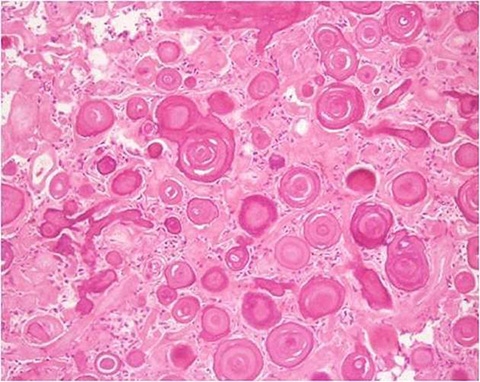

We were just talking about primary hyperparathyroidism, which is when patients have high calcium levels, high parathyroid hormone levels in secondary hyperparathyroidism. This usually happens with patients who have had a kidney transplant or need a kidney transplant. Patients with kidney failure can have very high parathyroid hormone levels because their body is constantly stimulating the parathyroid glands.

And in that scenario, all four of the parathyroid glands become very enlarged. The parathyroid hormone levels go up from a normal range of 70 to in the thousands. And a good percentage of those patients would benefit from an operation. But again, a lot of them never actually end up getting an operation because they’re waiting for a transplant and all these other things. We have a multidisciplinary clinic here, the Secondary Hyperparathyroidism Program run by Eric Kuo, that's geared towards taking care of those patients.

Adrenal

What about adrenal diseases?

For adrenal cancer, which is one of the deadliest cancers known to man—and for some of the more poorly differentiated thyroid cancers, which can be very aggressive—there are new chemotherapeutics and new directed therapies that are out there. Some of these take into account the genetic profile of the patient and can target therapeutics to their particular mutations.

For us, one of the big things we focus on is the technique for taking out adrenals. The standard way to do a run-of-the-mill adrenal operation nowadays is to do a laparoscopic operation where you go through the belly. We are one of the few institutions, I think, in the country, or in the world, that actually go through the back. It's called retroperitoneal laparoscopic adrenalectomy.

And the reason we do that approach is that the operative times are faster, usually half as long. When you think about it, the adrenal gland is sitting way in the back, right on the top of the kidney. If you go through the belly, you have to move a lot of stuff out of the way to get there. You have to move the intestines, the spleen, the pancreas. But if you go through the back, it's really just the kidney and the adrenal back there, so it's a much more direct shot. And so again, faster operative times, there are fewer complications because you're just interacting with fewer things, and patients recover faster.

Wow. Why isn’t this approach more common?

This approach started to gain popularity probably about seven or eight years ago. Like any new innovation, it takes a while to spread. The other thing for adrenal surgery, in particular, is that it's just not that common. We do probably 50 to 60 adrenalectomies a year here, and that’s for a high-volume center.

The statistics are that the average general surgery resident does 0.7 adrenalectomies during their training period. Most people will never do an adrenal operation—for us, from a surgical side, that's the big thing, our experience with that approach.

Are there any other methods for adrenal surgery being developed?

We actually have a robotic adrenalectomy program. With a robot, we can offer the same techniques through the belly or through the back, but we use robot assistance. And the robotic adrenalectomy has some advantages to it. What our robotic surgeons tell us is that it's actually easier to do patients who have higher BMIs because the robot helps eliminate some of the physical limitations when you're doing it laparoscopically. Jen, Eric, and Katie McManus run one of the handful of robot adrenal programs in the country.

Early Detection

How important is early detection of endocrine disease and cancers? How much does it factor into treatment options?

Early detection is important, but especially early detection done in a thoughtful way. So, here’s an example of what I mean—there was a New York Times editorial about this “tsunami of thyroid cancer.” Did you hear about this?

Oh wow, no, I haven’t. But the word “tsunami” is a strong choice.

The rate of thyroid cancer is higher in Asia, so they had a routine of screening everyone with an ultrasound once you got to a certain age. And if you do an ultrasound on everyone, you're going to find that 60 percent of the people have a thyroid nodule, and you're going to find lots and lots of small thyroid cancers. And for that reason, the rate of thyroidectomy was astronomical in Asia. But what they realized after a while is that those patients they were operating on probably didn't need those operations because they were operating on really small cancers.

Are many of these patients people who would benefit from active surveillance?

They sure are. So, this led to a huge backlash when the New York Times article said there's a tsunami, epidemic, of diagnosis of thyroid cancer. In the U.S., the rate of diagnosis of thyroid cancer increased some exponential amount, but the mortality of thyroid cancer remained exactly the same, suggesting that—and again, when you look at the new cases of thyroid cancer, most of those were small cancers, not clinically significant cancers—the conclusion that we all came to was that we were over-diagnosing thyroid cancer because people were getting ultrasounds at the drop of a hat. And we were over-treating it.

That’s what led to the American Thyroid Association redoing the thyroidectomy guidelines in 2015 and saying things like active surveillance lobectomy for small cancers.

From a screening standpoint, for parathyroid and adrenal, the problem that we have is sort of the inverse—the rate of adrenal incidentaloma, which is an adrenal tumor that's found incidentally on a scan that's being done for some other reason, it’s driving a lot of the diagnosis of new cases of adrenal disease. And most of those patients who have adrenal incidentalomas actually don't need an operation.

What does active surveillance involve for someone with one of these small cancers?

The thought is the same across the board—don't have a knee-jerk reaction and just take those things out because most of those patients don't need an operation. So, they'll get repeat blood tests and hormonal testing, and imaging every six months, that kind of thing. If it's non-changing, then you leave them alone.

The one thing to think about from a screening standpoint is actually parathyroid disease. So it's very clear that we underdiagnose and undertreat hyperparathyroidism.

When you look at system-wide databases, like the Kaiser system database and some others, patients will be shown to be hypercalcemic, have high calcium levels on blood tests, and they'll sort of linger around for many years before they are diagnosed and subsequently sent for treatment. So, we're definitely underdiagnosing and undertreating parathyroid disease. So, if you have a high calcium level, don't be content to just say, "Oh, it's nothing." Make sure that people are evaluating it.

What percentage of people with high calcium levels have a parathyroid issue?

That's a good question. It's probably pretty high, and it really depends on where you are. If you're in a hospital and you have high calcium levels, or if you're ill and you have high calcium levels, the odds are that you're going to have cancer of some sort. But if you're out in the wider world and generally healthy, if you have high calcium, odds are that you're going to have parathyroid disease.

It’s also important to keep in mind that the most frequent cause of abnormal labs is lab error. So you could have a high calcium level because of lab error, you might've just eaten a lot of calcium, or be really dehydrated. The important thing is that if you have a high calcium repeated with a parathyroid hormone, evaluate it going forward.

Research

Anything specific in the world of endocrine research that you're excited about?

There are a few things. First is the interventional endocrine trial I mentioned earlier. Jen is the primary investigator of that program. Currently, we're only offering interventional endocrine procedures for benign thyroid nodules. And our theory is that for small indeterminate lesions, which have a 20 to 30 percent risk of cancer, we can ablate them, and that is adequate treatment for those small lesions and low risk for cancer lesions. So Jen is running a clinical trial where we're trying to suss that out with longer-term data.

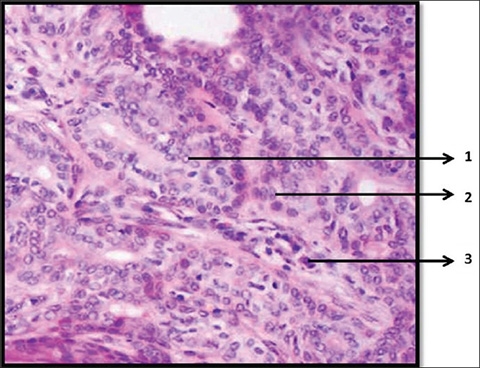

Number two is the advanced neural networks for the diagnosis of thyroid cancers. The way we evaluate thyroid nodules is we do a fine needle biopsy, and we look at the cells, and that gives a risk stratification for cancer. And then there are those indeterminate lesions that tell you that there's roughly anywhere from a 15 to 30 percent risk of thyroid cancer. And that's where molecular profiling comes in to try and help figure out further the risk of cancer.

When you look at those biopsies, the pathologist makes the decision as to whether or not it's in one of these six categories just based on the look of it. You would think that's a pretty precise activity, right? For example, there are classic findings for papillary cancer like Orphan Annie nuclei, intranuclear grooving, some psammoma bodies, all these things. And they all sound very definitive, pretty straightforward like it's a binary thing: you have it or you don't. But in reality, when you further parse out each of those findings, like in large nuclei, the real question is how large? How much bigger does it have to be? Two times, three times, two and a half times, 2.7 times?

When humans are looking at these slides, basically, we're doing Gestalt Theory. You're looking at it and you're saying, "Oh, that looks like thyroid cancer. I can't tell you exactly why, but I know that these nuclei are bigger than they should be. I don't know exactly how much bigger." A lot of it is just that gut feeling that the pathologist ends up having, but there are probably some very clear quantitative guidelines that you can actually use to apply.

Humans can't do all of those calculations on any given slide, we just physically can't. But computers can do it in a very easy, straightforward way. So, Jen and I have this belief that by using advanced neural networks and training them with thousands and thousands of biopsy samples, ultrasound data, and correlating it with the final pathology results from a surgical specimen, we can actually program the neural network to give us a better estimate of the cancer risk.

That is really cool. When you feed the network data and receive the result, what does it look like? What are you actually looking at?

Most of these medical advanced neural networks are what we call black-box networks. So, the difference between neural networks is that there's one called the algorithmic neural network, and the other is a black-box neural network—just colloquial terms. In an algorithmic neural network, you're telling the computer what to look for. You're saying that the difference between A and B should be one centimeter, and the difference between X and Y should be 10 chroma values or whatever it is. You're telling the computer the criteria that the computer should use. And the computer is just a dumb machine that parses it out.

In a black-box neural network, you actually don't know what the computer is doing. Basically, the neural network is saying, "Oh, of these 10,000 samples that I know are thyroid cancer, these are the things that are similar between all 10,000 of them. And then this is the next most similar thing. This is the third most similar thing." And it changes depending on where they are in the sample. In the first 1,000, it may say A is the most important thing. But then, in the second 10,000, it may have refined its network to say that, oh, actually, B is more important.

So, it’s constantly learning from everything you put in. Where are you in this process? How many samples have been entered?

We're doing the training of it now, so it's currently just Columbia. Our hope is that once we have the neural network that’s refined enough and it's fully multilayered with the training set, then we'll send it into a multi-institution environment where we'll get hundreds of thousands of samples from all over the country to try and validate it.

This could be the next big thing. The other reason it's great is because pretty much anyone can do a fine needle biopsy, can get a sample, but it takes some real expertise to interpret that sample accurately. So how great would it be just to do a sample, send it to a lab somewhere, and they say, "Cancer, no cancer." You start to eliminate that indeterminate group of lesions.

The thing that bums me out about being a thyroid surgeon is that we do a reasonable amount of thyroid surgery that we probably don't need to do because we're trying to figure out if something is cancer. If we can eliminate that category entirely, that would be ideal.

Dr. Kuo mentioned some interesting research in the prescription of narcotics for endocrine operations when we discussed RFA. Can you explain the work a bit?

This is something that I think is really, really exciting. We are looking at our narcotic prescribing practices because, as you know, we’re in an opioid epidemic, and there is some data to suggest that a reasonable number of people get addicted post-procedure. And in our type of surgery, thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenal surgery, it's all minimally invasive. But we try and minimize the amount of trauma and inflammation that patients experience, so we were prescribing narcotics routinely to everyone. And then Jen [Kuo] basically said one day, "You probably shouldn't be doing that. Your patients probably have minimal pain, and we can get them through using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. No narcotics." And that made a lot of sense to us as a group.

Basically, we stopped prescribing narcotics for all of our thyroid repair patients and we saw that there was no increase in phone calls asking for narcotics. Patients didn't balk at it at all.

That’s fantastic.

The most exciting thing is that Jen [Kuo] did a study using this database called Market Scan, which looks at the prescribing practices of physicians all over the country and looked specifically at narcotics prescribing practices after endocrine operations. Then she could tell how many narcotic pills people were prescribed, how many of those patients filled those prescriptions, and then how many patients became long-term users of narcotics.

She found that for endocrine procedures—specifically thyroid, parathyroid, adrenal—about 6 percent of patients end up being chronic narcotics users without another indication. So with both factors, the study showed that endocrine surgeons should just stop prescribing narcotics.

Wow, 6 percent. How does that number compare to other potential complications from endocrine surgeries?

Now, that’s the most interesting thing. Endocrine surgery is a very low complication proposition in experienced hands. When we talk about things for thyroid and parathyroid surgery, the main risks: are bleeding, infection, permanently hoarse voice, and permanently low calcium. They're all less than 1 percent.

What the Market Scan study is telling us is that if the permanent complication rates from these operations are less than 1 percent and the chronic opioid dependence is 6 percent in those patients who got narcotics—the highest complication that endocrine surgeons have is making opioid addicts. And so, we get to significantly impact patient’s lives by not prescribing pills.

That is so significant.

It’s a lot of people! Something like 120,000 thyroids are done a year—so six percent of that.

Over 7,000 people. Incredible when you actually look at the number.

Truly. It is!

My last question is about your goals. What are you looking forward to in the next 5 to 10 years?

At the end of the day, I think what I'm most excited about is that we are no longer hammers looking for nails. With RFA and active surveillance, and everything we’re doing, we have this whole toolkit that we can apply and make the treatment very appropriate to the individual patient. It's not just one size fits all. At Columbia, you are an individual patient with an individual set of concerns and we have a tool that can fit your lifestyle.

Our goal is to grow intelligently. When we talk about being a multidisciplinary center, it’s about having all of the experts and all the tools necessary to take care of patients. But part of that is also having it all in one place, and we're getting there. We have our endocrinologists here with us, but we want our radiologists here too. We don’t want you to have to leave this floor to get a CT scan.

Ultimately, it’s really about making the patient experience as good as possible, as comfortable as possible, and making it completely focused on the patients themselves. It sucks to be diagnosed with thyroid, endocrine issues, and our goal is to make it as nice as possible while you’re here.

Click here to learn more about endocrine diseases and treatments. To schedule an appointment at one of the Centers in the section of Endocrine Surgery please call (212) 305-0442.