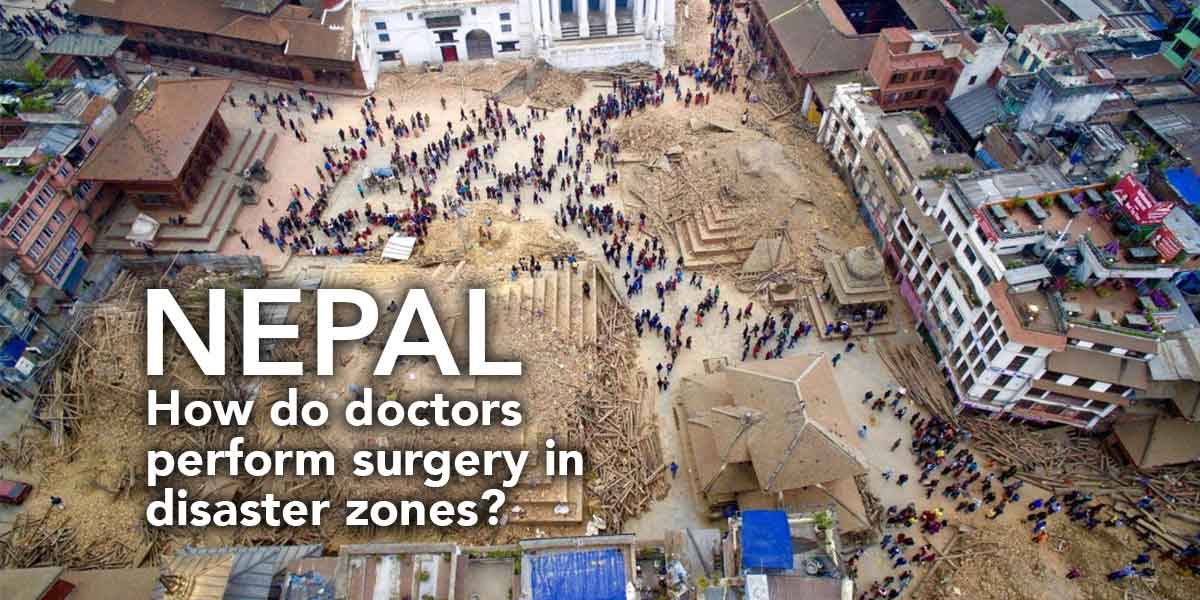

The news from Nepal is horrifying. The death toll has surged past 8,000 since the earthquake struck on April 25th, with more than 17,000 injuries and still thousands more people missing. This many people in need would greatly test even the largest, most well equipped hospitals. To add to this challenge, there’s intermittent electricity, no running water, and a shortage of even the most basic medical necessities. This begs the question: What can emergency personnel, especially surgeons accustomed to pristine operating conditions, do to save as many patients as possible? What sorts of improvisations are necessary to have a fighting chance in a disaster zone?

“In this environment, there’s a lot of injury and you’re triaging the people who are most likely to survive … you’re often prioritizing,” said Dr. Spencer Amory, Chief of General Surgery at Columbia’s Department of Surgery. When he isn’t working in a state-of-the-art facility in Manhattan, he’s found time to volunteer in a variety of low-resourced medical environments in the Philippines, Bolivia, Guyana, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti.

Electricity is unreliable. “In the hospitals that we work in, power outages are a regular event,” says Dr. Amory. “When electricity goes out, ventilation goes out, and a lot of these environments are very hot so both the team and the patient begin to heat up very rapidly. So what do you do? We have people moving old-fashioned hand fans to keep the heat down. Light goes out. We depend on operating lights, so you basically wind up operating with people holding flashlights to finish the procedures.”

Mechanical ventilation is another issue. In hospitals across the developed world, patients who are unable to breathe on their own are put on mechanical ventilators, allowing medical personnel to stabilize their breathing and allow health staff to treat other patients concurrently. In a disaster zone, the pressure on doctors’ and nurses’ time is even more pronounced, and with intermittent or non-existent electricity, unattended mechanical ventilation machines can become more of a danger than a luxury. According to Dr. Amory, in this situation “you use a series of people, family members even, to ventilate [using a hand pump], everybody taking a shift until they get tired and then another person takes over. You teach them how to do it.”

For most patients, stabilization and evacuation remain the primary goal. In fact, the best-case scenario for most patients in disaster zones is to have them stabilized long enough to evacuate them to an equipped hospital. This means stopping blood loss, securing fractures, and reassuring patients that they will soon be brought to safety. And in spite of transportation out of a disaster zone being hampered by destruction from the earthquake, for most patients who are not critically injured, even a prolonged evacuation still provides victims the best prospect for safe and effective treatment of their injuries.

“Ultimately, in these disasters, the key is flexibility,” says Dr. Amory. “Every situation is different but until the chaos is organized, you just work as hard as possible to stabilize as many patients for transport to a well-equipped hospital outside of the disaster zone. That’s how you make the greatest impact and save the most lives.”