By Lindsay Gandolfo

Key Takeaways:

- Living liver transplantation utilizes the liver's tree-like structure and its regenerative qualities, where healthy liver segments are transplanted to grow back in both donor and recipient.

- In the U.S., where 12% of those in need may die waiting and 13% become too sick, more living liver donations are a key vital solution to address the persistent shortage of deceased donors.

- While living liver transplants account for only 5-7% in the U.S., the procedure thrives worldwide, particularly in China where 90% of liver transplants are done through living donors.

“When I drive around or walk in the woods I’ve always got my eyes peeled for trees that have the shape of a liver,” says Jean Emond, MD, chief of transplantation at Columbia.

“It’s almost a little involuntary at this point,” he adds with a chuckle.

Dr. Emond spends most of his time operating on livers, and the liver has a strikingly similar architecture to that of a tree. They both possess intricate branching and natural adaptability developed to keep us toxin-free. Even more special, Dr. Emond assures me, is they both have the incredible ability to regenerate.

“See, the liver is asymmetric. Basically, two-thirds of the liver is the right lobe and the left lobe sort of sticks out,” says Dr. Emond as he makes a liveresque shape with this hands. “Every now and then you see a tree just like that. Exactly like a liver.”

When he’s not searching for the perfect liver-shaped tree, Dr. Emond is running the Living Liver Transplantation Program, a type of transplant surgery that relies solely on this special quality of liver regeneration. It works like this: you take a segment of a liver from a healthy person and implant it into a sick person. In a few months, the remaining liver in the healthy person grows back to the size it was before. The same goes for the recipient. The implanted piece of liver grows to the size of the previous liver, the size the body needs.

“Take a big tree with two main branches—if you remove part of the branch, the rest of the tree will enlarge. That's exactly what the liver does,” says Dr. Emond. “But if during that operation you damage any critical elements of the remnant, then you can either have a situation where the person is in big trouble and recovers, big trouble and dies, or big trouble and needs a transplant.”

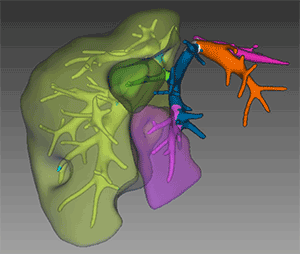

That’s why, with living transplants, liver matchmaking is so important. The planning process starts with analyzing the size of the recipient. Size determines which lobe will be removed, and architecturally there are only three options to choose from—the right lobe can be split into three separate parts, making three out of four lobes potentially removable. To do this, Dr. Emond maps out the liver with a color-coded 3D model.

A normal liver is roughly 2.5 percent of body weight in mammals, and if it gets below 1 percent the liver starts to struggle. Everything within these lobes fits together with incredible intricacy, and just like a tree, that intricacy must be accommodated. Four critical elements are at work: the bile duct system, the arteries, and the portal vein—elements that feed the liver. On the other end are veins that drain the liver.

“If someone my size has about a 3-pound liver I could easily donate a small piece to someone your size,” says Dr. Emond (I’m 5’6” and 120 pounds for context). “About a third of my liver would be enough for someone your size. So, these are the kind of adjustments we make when adults donate to adults.”

Most of the time in these situations it’s a family member or several family members who come forward to help out a loved one. But the donor must clear the second hurdle in the matching process: they must be healthy, and there’s no compromise on this. “We’re really looking at an exceptionally healthy slice of the population under age 60,” says Dr. Emond. “No chronic disease, diabetes, cancer, other serious diseases or conditions like drug addiction.”

As you may suspect, the matching process becomes much simpler when transplanting into small children, which are the bulk of living transplants done by Dr. Emond and his team. Liver donations where you only need to ‘trim the tree’ so to speak. “There’s a whole group of liver diseases that afflict babies, where the liver doesn’t form properly,” says Dr. Emond. “In those cases, a parent of almost any size can donate a very small piece, and we do those fully laparoscopic.”

“It’s really something. There’s no medication needed afterward and they go home that day. We’re probably the only place in the United States right now doing this operation [laparoscopically] where a parent can have just a very small set of incisions and donate,” adds Dr. Emond. “That’s run by Dr. Griesemer, he’s the head of our donor team.”

The first living liver transplant was completed here in the U.S., in a baby in 1989, and she’s still doing well. In fact, Dr. Emond has been at the forefront of living liver transplants since the beginning. He was one of the co-chairs of the landmark 13-year NIH study, A2ALL (Adult to Adult Living Liver Transplantation), supported by a consortium of 9 senators.

One would think that nearly 35 years later, living livers would account for a sizable portion of liver transplantation in the United States, but that’s not the case. In a country where 12 percent of people who need a liver transplant will die waiting for one and 13 percent will become too sick to undergo transplant by the time an organ is available, living liver transplants still only account for 5-7 percent of transplants.

It’s no secret that medical and surgical innovations require a trial rigor that grinds slowly, and for good reason. But that landmark 13-year study, based on the procedure first completed in 1989, started 12 years later in 2001. Before the clinical trial could officially begin, support had to be gathered, money secured, all of which adds years of delay to surgical advancement going mainstream.

In the meantime, living liver donation took off across the world. Yet, none of the valuable data from the hundreds of thousands of living liver transplants done in China, Korea, Taiwan, Japan, India, and much of the Middle East could be used in the U.S. study. They had to start from the beginning. Today, in China, 90 percent of liver transplants are done via living donors.

“In the U.S. and Europe, people are still really uncomfortable with the idea of any risk to the donor,” explains Dr. Emond. “We’ve sort of accepted it, embraced it, and promoted it as a necessary thing. It accounts for about 25 percent of the transplants we do here at Columbia.”

Dr. Emond would like to see that number increase, and he’s working hard to raise awareness about living liver donation. Thoughts on progress unfurl even as he strolls through the forest, finding inspiration in its wondrous canopy. “There are a lot of people who could be donors if surgical teams felt more confident that they could do it safely. And they can,” says Dr. Emond. “We think the number of people who die waiting for transplant is unacceptable. There’s really an ethical balance here that justifies swift innovation.”

Further:

- Robotics are Here for Complex Liver Surgery, and the Benefits Are Vast: An Interview with Dr. Jason Hawksworth

- How Close Is Xenotransplantation, Really?

- Pioneering Approach of Kidney Autotransplantation for Complex Kidney Disorders Offers Big Hope