By: Natalie Chang

Key Takeaways:

- Until recently, getting a timely liver transplant in the U.S. was uneven, with chances varying widely, especially based on location and demographics.

- In 2020, a game-changing policy broadened the area considered for liver transplants. Now, patients within 500 nautical miles of a donation site are eligible, focusing on medical urgency rather than relying solely on local Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs).

- The updated policy has resulted in more transplants, especially for critically ill patients. By moving away from strict reliance on local OPOs, the process is faster, reducing waitlist deaths. Ongoing data collection is needed to address any remaining disparities and improve equity in transplantation.

Imagine that you’re gravely ill, in need of a brand-new version of one of the most vital organs in your body: the liver. And the only real thing you can do is wait, and hope.

In the United States, until recently, your chances of receiving a donated liver within 30 days would vary significantly depending on where you lived—they could have been as low as 1 percent, or as high as 60. In fact, former Apple CEO Steve Jobs brought that disparity into national discourse in 2009, when he was able to receive a speedy liver transplant by putting himself on multiple waitlists, ultimately flying to Memphis for a transplant instead of waiting in California, where he resided.

For decades, experts and providers in the healthcare sphere have been pressing for a more equitable system of organ allocation, one that would even the odds between, say, a patient in a dense urban center with a long waitlist and a patient in a more rural, statistically healthier area with a short one. For almost 50 years, the system in place was an outgrowth of informal sharing networks between doctors and medical centers, resulting in a web of organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and donation service areas (DSAs) spread out across the country. One OPO and its DSA might be responsible for the donation needs of a few states; another might cover just one city.

The L.A. Times ran an in-depth story on the system back in 2006, showing how different transplant centers could capitalize on location and OPO boundaries—and how recipients with money and know-how could do the same. As time has passed, the differences between waitlist mortality rates in different OPOs have only become more stark, often falling along racial and class lines.

“OPOs are all different shapes and sizes,” says Jean Emond, MD, Vice Chairman of Surgery and Chief of Transplantation Services at Columbia University. “They’re a little bit like gerrymanders in Congress.”

Dr. Emond was previously the president of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and has also been involved with the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a national private organization that manages the organ transplantation system in the U.S., for years. “I was involved in a number of UNOS committees over the years that were addressing, or trying to tackle liver distribution,” he says, pointing out that the demand for donated livers became so high in the ’90s, and leading opinions so polarized, that people still refer to the era as “the liver wars.” “You had a situation of scarcity where rationing had to take place.”

The community was torn about how best to distribute and allocate livers that were eligible for donation. “Our ranks were bitterly divided,” Dr. Emond recalls, remembering his visits to hospitals and transplant centers all over the country to hear from and debate with stakeholders. “And I tried my damnedest to steer a middle ground and keep people together and preserve the collegiality and the partnership. But at the same time, we really needed to push the envelope towards broader sharing.”

Dr. Emond’s efforts, and those of many other advocates, were recently rewarded with a new liver distribution policy, first adopted by UNOS in 2018. After spending some time tied up in federal courts, the policy was finally approved and implemented in early 2020.

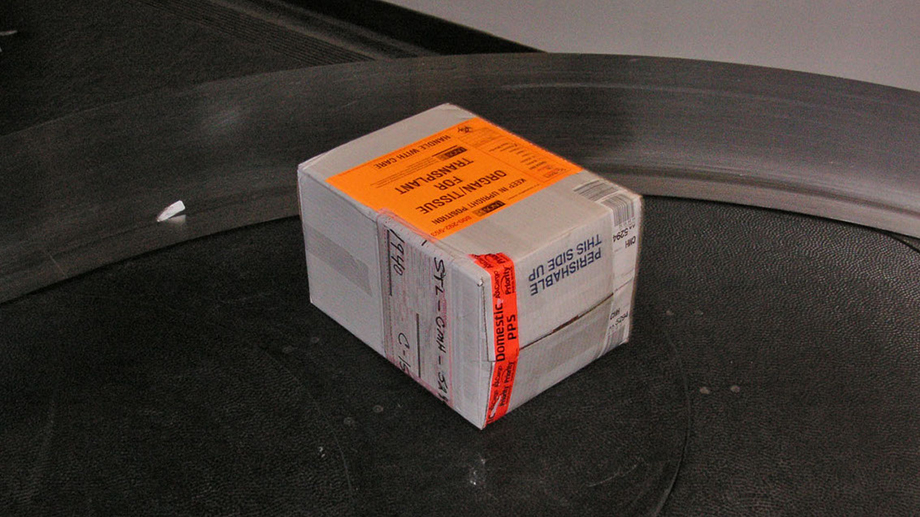

The new policy means that patients who need livers will no longer be solely reliant on the OPO in which they happen to live—which again, might be responsible for anything from multiple states to just one town. Rather, when a liver becomes available for donation, patients within a 500-nautical-mile radius of the donation hospital will be considered as recipients, and ultimately selected based on the severity of their medical need.

“What happened for us in New York is that we immediately were exposed to a much larger geographic area of organ donors,” says Dr. Emond. “So we were able to see more transplants and do more transplants.”

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed transplants for some of the year, as NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s ICU reached capacity. But by the end of the summer of 2020, Dr. Emond saw firsthand what the new policy enabled. “Our very sickest patients got transplanted within days, and then we were exposed to a lot of offers for less sick patients that we wouldn't have seen otherwise,” he says. “And so what happened is, through the first two thirds of 2021, we've done more transplants than we have in a long time, and we're on pace to do more liver transplants than we ever have at NewYork-Presbyterian.”

The policy is still so new, he emphasizes, that data on its effects still needs to be collected and analyzed. “But certainly my qualitative sense is that the sicker patients were being transplanted faster, and the waitlist mortality has decreased.”

Why, then, did some oppose the new policy? In short, less-populated areas with larger supplies of organs were concerned that their supply will now be accessible to nearby cities with higher demand. “The centers that didn't want to change the rules were clearly benefiting from the status quo,” Dr. Emond reminds us, pointing out that sicker patients will still be more likely to receive transplants than healthier ones under the new policy.

Still, he knows that the new policy won’t be perfect, and that updates in other arenas still need to be made. The OPOs, for example, “are basically monopolies. They’re not for profit, but they’re allowed to charge money for every organ they recover to cover their costs—and their costs include gleaming headquarters and large CEO compensation packages.” Congress recently passed legislation to increase and improve federal oversight of the OPOs, ensuring that their funds (which ultimately come from taxpayers) will go toward improving and expanding organ procurement.

As for the liver policy, Dr. Emond has seen that it’s a significant improvement over its predecessor, though he’s hoping it will continue to evolve. “We still need to see data to tell us where the disparities persist,” he says. “One of the things that people had spoken in favor of was the map considering population density, or that when you live on a coast, it means your circle is only half as big as in the middle of the country. Those are the kind of things that are going to be tweaked as data comes in.”

He also points out that more research and work must be done to address racial disparities in transplant access, access to Medicaid and insurance that covers the transplantation process, and more. “As with most forms of healthcare in the United States, people of low socioeconomic groups, minorities, African-Americans, Hispanics, Latinos, have been disadvantaged in access to the waitlist. There’s a lot to this, if you start pulling at the strings.”

Transplantation may seem like a relatively niche area of health care. But to Dr. Emond’s point, it’s also where groundbreaking science and technology, socioeconomics, race, and policy intersect. “Transplantation is one of the most advanced manifestations of science and healthcare capability. It's an incredibly powerful tool for saving, prolonging, and improving the quality of lives. It's also obviously a rather expensive form of health care, and the public has a right to know that healthcare dollars are being used in a way that is giving the most life benefit for the value that's spent. So transplantation is a great paradigm, a great model for understanding both the amazing potential of health care and the discouraging limitations of how we deliver health care in the United States.”

Transplants may not be the most common medical procedure, or the most flashy. But as Dr. Emond reminds us, every life affected by any illness is one part of an interconnected web of human beings. “Admittedly, transplantation doesn't affect a large number of people. And yet by the domino effect, it affects hundreds of thousands of families who have loved ones, children, relatives, and friendships. So if you start to collect the circular effects of saving a life, or failing to save a life, it starts to really matter.”

Further Reading:

- Unbreakable Bonds: The First Robotic Kidney Transplant Is a Testament to Lifelong Friendship

- By Letting Patients Lead, We Can Advance Medicine

- Caracas to Santo Domingo: Creating Access to Pediatric Liver Transplant from the Ground, Up