A Q&A with Dr. Jeffery Zitsman, Director of the Center for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery

Obesity is a national epidemic, and it’s affecting our children at an alarming rate. The CDC reports that 1 in 5 children from age 2 to 19 is overweight. Today, some 2 million teenagers suffer from severe obesity. And Dr. Jeffrey Zitsman, Director of the Center for Adolescent Bariatric Surgery, declares they are all candidates for weight loss surgery.

That may sound shocking at first, but weight loss surgery is proven to be the most effective treatment for severe obesity in adults and adolescents. Procedures fall under two types: restrictive surgery or a combination of malabsorptive and restrictive. Restrictive surgeries limit the amount of food the stomach can hold, and the malabsorptive effect keeps some nutrients and calories from digesting fully into the body.

While it sounds like the intervention itself is a solution, weight loss surgery is not a cure. You won’t shed pounds instantly without rigorous lifestyle changes. But for those who have been unsuccessful with diet and exercise alone, the difference is your body is set up to succeed. Surgery works as the jumpstart to a medical weight loss program; it can normalize metabolism. Suddenly, all those lifestyle changes matter and the results are built to last.

For kids with severe obesity, early intervention provides immense health benefits. But what does the journey entail? Dr. Zitsman sheds much-needed light on the childhood obesity epidemic and the ways effective treatment can reverse the trend.

Let’s start with the cause of this epidemic. Why are a record number of teenagers struggling with obesity now?

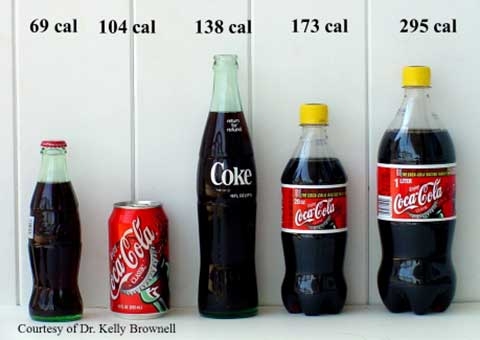

For one thing, portion sizes have grown much larger. Over the past 15 years, the size of a bottle of Coke has gone from 6 oz to 1 liter. We also have super-size meals and foot-long sandwiches. Without realizing it, our kids are consuming more.

On top of it, meals are more calorie-rich thanks to the addition of high fructose corn syrup and salt. These additives also make kids hungry, so they want to eat more. Many never feel fully satisfied, but they’re being chemically programmed to snack constantly.

And food is available everywhere. There are vending machines in schools, convenience stores on every corner, making it really easy for kids to get snacks and chips and candy bars whenever they want.

Our children are eating bigger portions, eating more often, and they’re chemically stimulated to keep on eating. It’s the perfect storm.

At what age can obesity start?

Some children are significantly overweight at birth. Others develop obesity in infancy from the formulas they’re fed, the amounts they’re fed, and the early introduction of high-calorie foods into their daily diet.

There are also several “bumps” in a child’s life when they’re likely to gain weight. The peak times are in preschool, age 2 to 5. Then age 7 to 8. And finally, at the start of middle school, at age 10 or 11.

Most childhood obesity is related to overeating—though there can be other factors, some kids take steroids for asthma and parents often attribute a sudden weight gain to that medication.

When it comes to adolescents and teens, what does the surgery involve?

Our approach has shifted in the last decade. Back in 2007, we felt adjustable gastric banding, a “restrictive” procedure, was appropriate for adolescents with the most serious weight problems. That’s where a band is placed around the top portion of the stomach, restricting the amount of food a patient can eat. And at any point, that band can be removed, and there is very little impact on nutrition. Our teens started losing weight, but not as much as adults who had received a gastric bypass.

Gastric bypass is a combination type operation that divides the stomach into a small upper pouch and a much larger lower "remnant" pouch. The small intestine is then rearranged and connected to the small pouch. There’s limited space for food intake, and the rerouted intestine allows food to bypass part of the intestine that way some calories and nutrients go unabsorbed. For a while, this was appealing—

Then in 2010, the first report came out on yet another operation for adolescents, the gastric sleeve. Results were almost as good as the gastric bypass and patients had fewer complications. This operation removes approximately 75 percent of the stomach leaving a tube or "sleeve" which holds much less food. With this data, we began to offer our younger patients the sleeve procedure. To date, we have performed approximately 250 of them.

Why isn’t surgery alone enough to lose the weight?

I feel that changing abnormal eating behavior is the most important part of losing weight. The gastric sleeve operation helps limit your intake of solid foods, but if you keep up the high-calorie drinks, you won’t lose enough weight. The one big habit you’ll have to change right away is replacing high fructose “juices” and sodas with water and diet drinks. Before you go into surgery, we start working on behavior change. You’ll have to start reading labels, and if a beverage has more than 25 calories per serving, put it back.

We spend a lot of time coaching patients, walking them through the finer points of lifestyle change. It’s like learning to play a musical instrument or mastering a sport. Our message to teens is this: You have to be full partners in the weight loss process.

The other take-home message is to do this with a friend. Over the years, we’ve learned a lot about the value of peer support. We give teens the opportunity to meet others their age who have had a bariatric procedure. One of our medical students is working on a project we’re pretty excited about—a computer app to help our patients set up a buddy system and work toward their weight loss goals together.

For a child with severe obesity, is adolescence the age to seek surgical treatment?

No, not necessarily. We’re one of the few centers in the country that operates on young children. For years, experts worried that a weight loss operation would be bad for kids who hadn’t reached their full height because their growth plates might close prematurely. But recent research shows these kids soon catch up and have a normal growth curve.

Bariatric surgery can help with other medical conditions such as insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Idiosyncratic intracranial hypertension is a neurological disorder resulting from the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. This can lead to severe headaches and loss of vision. We treated a nine-year-old with this condition! The patient was also suffering from migraines and obstructive sleep apnea and needed a machine to help with breathing at night.

After weight loss surgery, the results were dramatic. The child’s weight dropped, the spinal pressure returned to normal, the headaches improved, and the patient no longer needed breathing assistance and went back to a normal sleeping routine.

What about other health problems associated with obesity?

Obesity fundamentally accelerates the aging process; it affects everything. The diseases we see in severely overweight teens—type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, bone, and joint problems—are all afflictions of the elderly. I warn families that if their kids have obesity, they are being set up for cancer and heart disease. Yet with weight loss, those conditions can often be reversed.

Can you predict when and how these illnesses will develop?

No, because not all adolescents react the same to carrying all that extra weight. We may have five patients the same age with same elevated BMI (body-mass index) that all react differently. Three may have no symptoms; one may be pre-diabetic and also have high cholesterol, the last one may have abnormalities in the bones of his legs.

An individual’s reactions to weight can also change over time. This week, I saw a boy with BMI of 45, and he had no symptoms at all. But on a previous visit when he was much heavier, his cholesterol was high, and so were his liver enzymes. There really is no set formula. That’s why we have to monitor our pediatric patients very carefully and personalize weight loss programs.

To that end, what do we know about the causes of obesity? Do genes play a role?

Obesity does appear to run in families, but families also tend to eat the same. Is it genes or the environment? Probably a bit of both.

When identical twins are raised apart, they end up close to the same weight. Yet there are families I’ve taken care of who have three normal weight kids and the fourth one is significantly obese. Neither of the parents is overweight, and that last child is an outlier.

Genes play a role in how obesity develops, and also in how it manifests, but it’s just one of many things we consider. Metabolism is an important factor. Some adolescents don’t burn calories that quickly. Others are literally hungry all the time. Teens may have psychological issues that lead them to overeat. If they’re anxious or depressed, food can become like a drug.

And then there’s the microbiome—the flora in the intestines. It varies from one person to the next, and research suggests that it contributes to weight balance. Lifestyle changes contribute too. These days, people tend to cook less at home and eat out more often, and fast foods have more sweeteners and a lot more salt.

As a nation, we are also moving less. Kids don’t do as many outdoor activities as they used to, they’re getting too much screen time. Instead of walking over to see a friend, they text. The overall calorie burn is going down not just for kids, but for all of us.

That brings us to the social aspects, is the stigma around being severely overweight a factor?

Stigma and weight discrimination can be devastating and have lifelong effects. Most of the adolescents we see live with high stress, they are concerned about how they look and whether or not they fit in. They want to be able to wear the same clothes as their friends. They may have been bullied frequently and feel isolated. The emotional toll is incalculable, and to some degree, their self-image is damaged by obesity.

After surgery, many kids tell me they are more self-confident, have more energy, and feel better about themselves. It’s greatly satisfying to know we have helped them do that.

That stigma translates more globally too. Why aren’t we doing more, as a nation, to prevent obesity?

The problem is many Americans still think of obesity in terms of personal responsibility and blame. If you did a poll asking, “What’s main reason for obesity?” an overwhelming majority would say, “Oh, some people are just lazy, and they don’t eat right.”

People need to understand that this is a complex problem that can start in infancy, not the result of a lack of willpower.

What’s your most important piece of advice for parents of an overweight teen?

Watch what your child drinks. Without realizing it, children can get hooked on sugary “juices” and sodas and gain a lot of weight.

New York City tried to tax sodas made with high fructose corn syrup, but the measure was defeated. From a health standpoint, this was exactly the right move—other countries have done this and have seen a decrease in obesity rates.

Lastly, what kind of life can young people look forward to after bariatric surgery?

A healthy one. Many have a procedure then go off to college or start their jobs. The vast majority lose between 60 and 70 percent of their excess weight in the first few years. We help them to transition to a new physician and also track their progress as best we can. Losing weight will not solve all of their problems, but it certainly helps. The good news is that over time, our young patients tend to maintain their lower weight and continue to improve their health.